Have you ever wondered how an examiner determines “strangulation” as the cause of death?

Asphyxial death by suicide, accidental death, and homicidal strangulation can be difficult to determine without context clues. Thankfully, investigators are often trained in the differences to process death scenes properly. More importantly, forensic pathologists and medical examiners are trained to go beyond the crime scene and determine when strangulation is the cause of death.

Most reported murders by asphyxia involve strangulation.

Strangulation can be divided into three subcategories: Manual Strangulation, Ligature Strangulation, and Hanging. The distinction between these three classifications is attributed to the cause of the external pressure on the neck.

What is Manual Strangulation?

Manual Strangulation is when a violent offender attempts to or does take someone’s life after applying pressure to the neck using their bare hands. The process of manual strangulation is a physically demanding one, and offenders are often men, while victims are their female intimate partners

According to the Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention, “A woman who has suffered a nonfatal strangulation incident with her intimate partner is 750% more likely to be killed by the same perpetrator…with a gun.”

Nonfatal strangulation has been reported in nearly 45 percent of attempted homicides in domestic violence situations against women, and 97 percent of victims are strangled manually. It concerns many experts, considering it represents a sense of physical control that is a risk factor in homicides against women.

What is Ligature Strangulation?

Ligature strangulation is a form of asphyxiation that involves the use of a cord, rope, wire, or other similar material to apply pressure to the neck, cutting off the blood supply and oxygen to the brain.

In a study out of Finland, researchers found that out of 59 homicide strangulation cases, 66 percent were manual, 17 percent involved a ligature, and only 5 percent involved both. They theorized that ligature strangulation cases are less common because they require more forethought and for an offender to bring the ligature with them.

Understanding Hanging

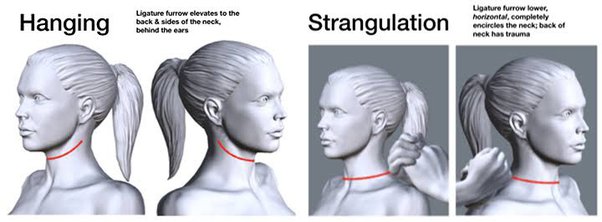

Hanging is a form of asphyxiation that occurs when a person suspends themselves or is suspended against their will from an object using a ligature around their neck. The, with the gravitational weight of their body constricts the band around their neck, resulting in death. Hanging can be either accidental, suicidal, or homicidal — and it’s up to the pathologist to assess the internal and external injuries to make that determination.

Hanging vs. Autoerotic Asphyxiation

Accidental Autoerotic Death (AAD) is defined as a solitary, accidental death caused by a lethal paraphilia such as hanging, strangulation, invert suspension, or plastic-bag asphyxiation. This type of strangulation relies heavily on context clues and death scene characteristics to exclude the possibility of sexual homicide or suicide as the manner of death. One of the tell-tale signs of this will be the location. It’s often a secluded area with items and evidence chosen for the autoerotic performance is usually secluded, with evidence of repeated autoerotic behavior.

The FBI estimates that between 500 and 1,000 people die each year in the United States from Autoerotic Asphyxiation.

Though it may seem that context from the crime scene is enough to distinguish an AAD from homicidal strangulation, some organized offenders may engage in crime scene staging, which is the purposeful alteration of crime scene characteristics for the exclusive purpose of misdirecting authorities. Suicidal and Accidental Asphyxial Deaths likely will not show the same types of defensive wounds displayed by homicide victims (nails, bruise locations, etc.), and the ligature marks around the neck are slightly different in nature.

Reading Ligature Marks Externally and Internally

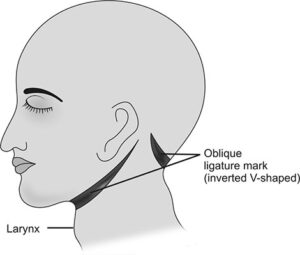

In cases of suicidal asphyxiation, ligature marks are oblique, or slanted, and are largely only seen near the front part of the neck.

Example of a suicide ligature mark

However, in cases of homicidal asphyxiation, ligature marks are horizontal and completely encircle the neck as a result of an offender holding a ligature around the anatomy. The post-mortem markings, otherwise known as ligature furrow, can be found either above or below the thyroid prominence (Adam’s Apple), whereas, in suicidal asphyxiation, ligature furrows are generally above the thyroid prominence and tend to angle up along the jawline slightly.

Additionally, where the ligature furrow meets in the back of the head, in most cases, the furrow marks tend to come together at one point, whereas with a homicide, there appears to be a crossing of the ligature mark. Furthermore, compared with other forms of homicide, autopsy evidence of Strangulation is frequently found with other life-threatening traumatic injuries.

Furthermore, compared with other forms of homicide, autopsy evidence of Strangulation is frequently found with other life-threatening traumatic injuries.

A retrospective study using data collected over a twenty-year period from a major (European) city showed that very few strangulation homicides showed no signs of internal injuries, but over half of all reviewed suicides did not show evidence of internal injuries. Further, in cases where the manner of death was classified as suicide, internal neck injuries were usually limited to the sternomastoid muscle. Supporting these findings, another study found macroscopic bleeding in the laryngeal muscles of the homicidal strangulation group, but found none in the suicidal strangulation group.

There is also a much higher occurrence of fractures in the neck (to the thyroid horns and the hyoid bone) in homicidal strangulations as well as additional trauma to the head and neck.

When petechial hemorrhages, or ruptures of (microscopic) capillaries, occur in cases of strangulation, they are almost always distributed above the level of neck obstruction and distal to the heart, which should be noted in their report. However, while characteristic of these cases, petechial hemorrhages are not particularly diagnostic or helpful in distinguishing a cause or manner of death, as they are a relatively common nonspecific autopsy finding.

Love this post? Meet the Author.

Nadia Yassin is a Case Researcher and Content Contributor Extern at Uncovered, where she aggregates research on unsolved cold cases and assists with the twice-weekly newsletter, The Citizen Detective. Nadia is completing her Master of Arts in Forensic Psychology from John Jay College of Criminal Justice, where she focuses on investigative psychology and the behavior of violent criminals. Nadia believes that knowledge, attention, and compassion are key to building a brighter future.

Uncovered is building a community around collective impact for cold cases and supporting further education to develop citizen detective skills. Interested in contributing? Join our community, or reach out with a topic you’d like to share with our readers.