By: Andrea Cipriano, MAFP

Now in her 80s, Dr. Burgess remains dedicated to victims and telling their stories. She believes that by peeling back the criminal mind, their chilling insights can hopefully save future lives.

Dr. Burgess spoke to 3,000 CrimeCon attendees about her work understanding criminal behavior.

“Why do serial killers kill?”

Before Dr. Ann W. Burgess set out on a quest with her team at the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit to pioneer our current understanding of criminal offenders, Burgess was a budding nurse, asking herself a different question.

“What is the impact of trauma on rape survivors?”

Even though Burgess has become known for her highly regarded work in the field of forensic psychology and law enforcement, she shared that growing up in the 1950s, girls had two main career choices: becoming a teacher or becoming a nurse.

She never imagined her clinical work would lead her team into some of the most terrifying prisons across the county to sit across the table with infamous killers.

While Burgess says this, the 3,000 CrimeCon attendees at her convention lecture all leaned forward in their seats.

CrimeCon is an immersive three-day experience for true crime fans, creators, and leading industry professionals. With a heavy focus on education, CrimeCon features speakers, panels, breakout sessions, and hands-on experiences to allow interested people to step behind the yellow crime scene tape — even if it’s just for a long weekend in Orlando.

At her breakout session, Dr. Burgess took attendees behind the scenes of her life peeling back the criminal mind, and revealed some of her groundbreaking insights. But, before her career was fictionalized in Netflix’s Mindhunter as Dr. Wendy Carr, Dr. Brugess was passionate about changing the way law enforcement officers understood rape, and treated survivors of the awful crime.

‘The Rape Victim in the Emergency Ward’

Professors Ann Burgess, left, and Lynda Holmstrom, right, in 1972 (via University Archives)

While working as an assistant professor at Boston College in 1969, Dr. Burgess shared with the CrimeCon audience how she was introduced to Lynda Lytle Holmstrom, a sociologist. Holmstrom shared that she was interested in publishing a study about rape survivors since, at the time, it was common for women to be blamed for what happened to them.

Together, they created a counseling program at the Boston City Hospital that would allow them to interview rape victims once they were admitted for care.

Dr. Burgess told the CrimeCon crowd that for an entire year, Burgess and Holmstrom would drive to the hospital when they got a call that a victim was admitted — often in the middle of the night.

By the end of their research, they interviewed 146 rape survivors, ranging in age from 3 to 73, and published their findings in a 1973 American Journal of Nursing article titled “The Rape Victim in the Emergency Ward.”

Some of the groundbreaking conclusions are concepts many would think are common sense today — but it wasn’t seen that way back then. Dr. Burgess and Holmstrom detail how survivors expressed wanting to feel clean by washing up and using mouthwash. Victims said other simple items like cigarettes for anxiety, clothespins for torn clothing, and tissues for tears would’ve fundamentally changed their healing experience.

Victims were never looked at in this caring and empathetic light before.

Boston College notes that their paper also introduced the term rape trauma syndrome, which is still used in forensic settings to describe the physical and psychological reactions of victims, such as “anxiety, humiliation, muscle tension, and self-blame.”

The groundbreaking nature of the paper had another unintended major impact on Dr. Burgess’s career — the FBI wanted to know more.

Dr. Burgess (1984)

‘No Shoebox Research’

When the FBI came calling, it was then-Director William Webster himself who invited Dr. Burgess down to Quantico, Virginia in 1978. He wanted her to teach agents in training about the importance of talking to victims to learn more about the offenders.

When Dr. Burgess was finished teaching the students, she’d spend the afternoons with other agents talking shop. It was then that she met FBI agents John Douglas and Robert Ressler — both who had already begun trying to understand the criminal mind by conducting interviews with serial killers.

The group began a ritual of sorts… class in the mornings, and unsolved cases for the rest of the day.

Dr. Burgess shared with the CrimeCon crowd how they’d discuss evidence collected from crime scenes to try and glean information about the illusive offenders roaming the country.

Pretty soon, the team was formalizing a plan to record and publish their research for it to be taken seriously.

“We were told ‘no shoebox research!’” Dr. Burgess told the crowd, explaining how their supervisors said they weren’t interested in any research that would get put in a box, waste away funding, and never get published.

Dr. Burgess was determined that this study was going to transform the industry — and that it would give her the opportunity to speak for the victims.

Meeting the Monsters

Dr. Burgess (at the computer) and Special Agent Robert K. Ressler

At the end of the team’s study, they had personally interviewed 36 sexual killers from 20 state prisons. Seven of the offenders were convicted of killing one person, while the other 29 offenders were convicted of killing multiple people.

“There were a total of 118 confirmed victims for our study,” Dr. Burgess shared. “We suspected that number is really as high as 200 or 250.”

Famous serial killers interviewed included Edmund Kemper, Donald Harvey, Joseph Paul Franklin, Ted Bundy, David Berkowitz, John Wayne Gacy, and Jerry Brudos — some of whom appeared in the first season of Mindhunter.

In speaking with Dr. Burgess after her presentation, she told me she believes to this day that there are dozens of serial killers and rapists that have victims that haven’t been officially tied to their offenders.

“There’s going to be extra cases,” she said.

Throughout Dr. Burgess’ presentation, the CrimeCon crowd was so invested and silent — you could hear her light footsteps as she slowly paced on the stage.

Toward the end of her breakout session, Dr. Burgess showed the crowd exclusive interview clips with notorious offenders.

Everyone’s attention was pinned to the big screens, taking in the grainy images and crackly 1980s audio of men with no light behind their eyes discussing their horrific behaviors like they were rattling off a grocery list.

Two-Sided Parts

When I spoke to Dr. Burgess after her presentation, she recalled profiling killers like John Joseph Joubert IV, who was just 6 years old when “troubling thoughts began…about killing and eating his babysitter.” Tracing back to formative experiences helps explain these criminals’ actions, though Dr. Burgess cautioned, “It’s really hard” to fully “get into their heads.”

Joubert was just 16 when he stabbed a pencil into a six-year-old girl — and years later when he was 19, he went off to assault and murder three boys in Maine and Nebraska. Joubert was a young sexual serial killer in the making, and when Robert Ressler worked with officers in Maine to connect the cases, the FBI team knew they needed to interview him.

“So many of them led normal lives before they actually became the killers that we know them as,” Dr. Burgess told me. “And they have this two-sided part of them.”

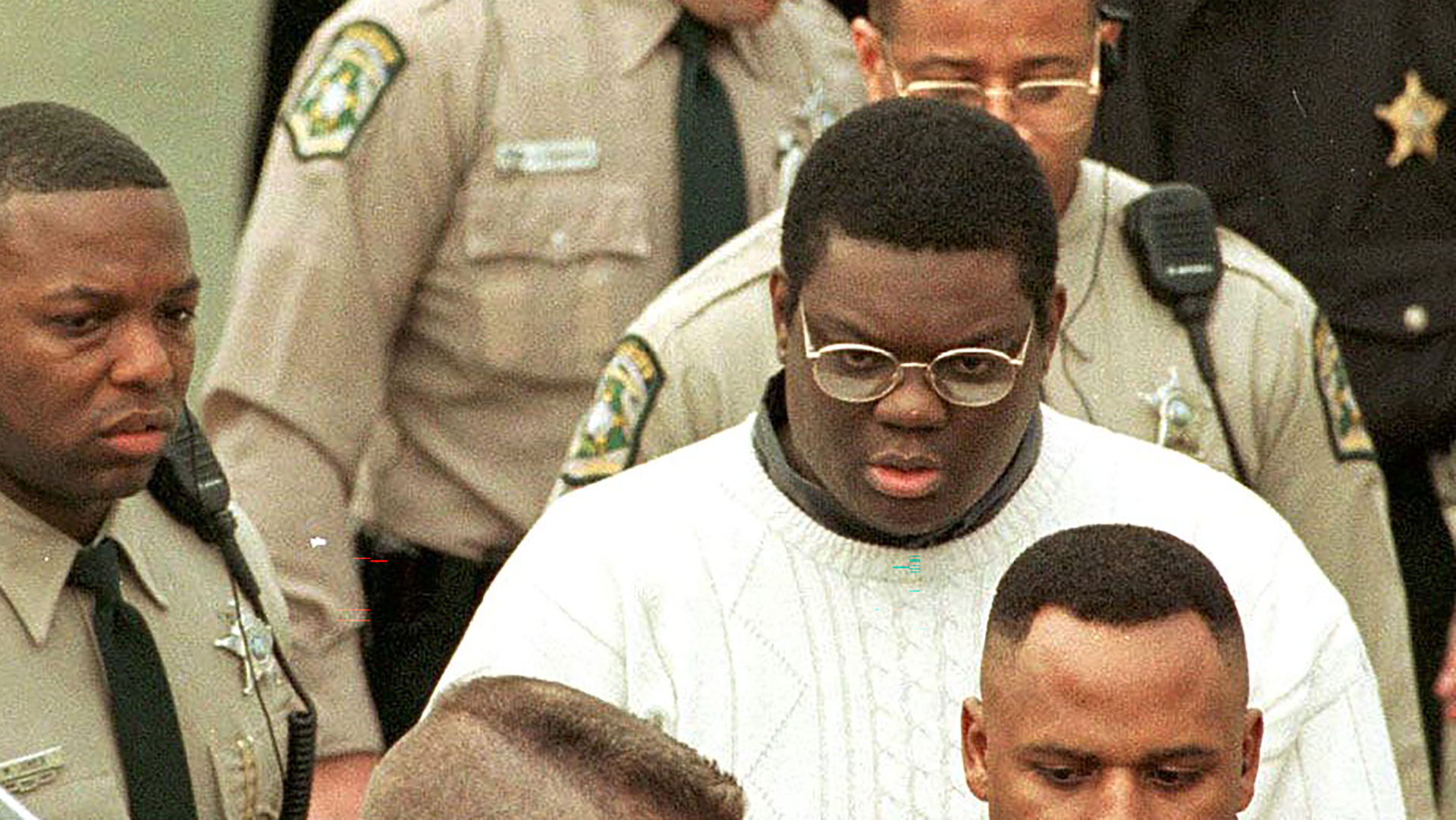

That two-sided part was apparent with another offender she discussed in her presentation: Henry Louis Wallace.

Wallace was known as the “Taco Bell Strangler.” He killed 11 Black women in South Carolina and North Carolina over a span of 4 years, ending in 1994 when he was arrested. People who knew him said he was “charming and smart” but when he would flip a switch, he became blinded with rage.

“There are two people — the good and the bad Henry,” Dr. Burgess began. “It’s not unusual for a killer to say this. They like to compartmentalize themselves. Dennis Rader, he uses the word cubing to describe this in himself. I think it’s trying to justify that they’re not a horrible person — but they are.”

Dr. Burgess went on to note how even Wallace was metacognitive enough to tell investigators that he had a “bad side.” He says it was fueled by years of abuse by his mother and twisted sexual fantasies.

When I asked Dr. Burgess if there’s a particular case that sticks with her, she said while they all do, cases with a specific cause of death bother her the most.

“The most personal, of course, is your strangulation cases,” Dr. Burgess explained. “The [killers] who use their hands and say, ‘I needed to look into their eyes and see them — I wanted to be the last person that would see them suffer,’… It’s really creepy.”

“They all stay with you,” she said.

Now in her 80s, the FBI legend continues to explore new frontiers in understanding serial killers, hoping to extract insights from their writings and art to prevent future tragedies. Decades into her career, Dr. Burgess’ passion for profiling through meticulous research remains undimmed.

“No shoebox research!” she echoed to me as I was leaving our interview — a mantra that has made her invaluable to generations of investigators.

Love this post? Meet the Author.

Andrea Cipriano is a Case Researcher and Content Specialist at Uncovered, where she writes for the weekly true crime newsletter, The Citizen Detective. Andrea graduated with a Master of Arts in Forensic Psychology from John Jay College of Criminal Justice where she focused on researching and peeling back the criminal mind. Andrea believes that it’s never too late for justice.