The pursuit of criminals has intrigued detectives, scientists, law enforcement officials and everyday crime sleuths for centuries. As part of that quest, many have developed methods, techniques and tools to find answers to the age-old question “Whodunnit?”

While the use of some approaches, including DNA analysis and camera surveillance, have been refined and expanded over the years, others have been outright debunked or come under scrutiny for being ineffective.

The pursuit of criminals has intrigued detectives, scientists, law enforcement officials and everyday crime sleuths for centuries. As part of that quest, many have developed methods, techniques and tools to find answers to the age-old question “Whodunnit?”

While the use of some approaches, including DNA analysis and camera surveillance, have been refined and expanded over the years, others have been outright debunked or come under scrutiny for being ineffective.

Here are 4 crime investigation tools and methods that have come and gone throughout the history of criminology, or have been questioned as dubious.

Bertillon System

In 1879, Alphonse Bertillon, a French criminologist, developed a universal technique for identifying suspects and criminals based on physical measurements. It was considered comprehensive and incredibly effective. Law enforcement officials worldwide, including those in the United States, implemented the Bertillon System as part of their day-to-day operations. Criminals and suspects were measured based on their standing height, sitting height (length of trunk and head), distance between fingertips with arms outstretched, and size of head, right ear, left foot, digits, and forearm. They also captured and noted distinctive personal features, including eye color, scars, and deformities.

It was widely accepted until May 1, 1903. That’s when an African-American man by the name of William West was being processed at the U.S. Penitentiary Prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. When he underwent the Bertillon System process, West was identified as a person who had already been processed under the anthropometric method. His measurements seemed to match up with a profile already in the system.

Not only did he seem to have the same measurements, the photo and name seemed identical. When the identification clerks realized that another William West was already imprisoned, they had to believe that the West before them was telling the truth when he said he had never been imprisoned. A comparison of their fingerprints confirmed that they were indeed two different people.

The news shook law enforcement officials globally. It didn’t take long for fingerprinting to be viewed as a more reliable method than the Bertillon System, no matter how rigorous it seemed. In further research, it was noted that the identification of the two William Wests did reveal a discrepancy of 7 mm in the length of the men’s feet. However, the Bertillon System was debunked and eventually permanently phased out as a reliable investigative tool.

The Born Criminal Theory

Measurements also were at the core of an Italian criminologist’s theory — “Born Criminal,” which made the case that you could tell if someone was a criminal or was likely to turn to criminal acts simply by the way they look. Cesare Lombroso’s theory, which was published in 1876, said that a distinct biological class of people — those with atavistic or primitive features — were prone to criminality.

After studying the features of 383 dead criminals and 3,839 inmates in Italian prisons, Lombroso came up with these “born criminal” categories:

- Features of a thief: Expressive face, manual dexterity, and small, wandering eyes.

- Features of a murderer: Cold, glassy stares, bloodshot eyes and big hawk-like nose.

- Features of sex offenders: Thick lips and protruding ears.

- Features of women offenders: Shorter and more wrinkled, darker hair and smaller skulls than ‘normal’ women.

So many came forward to dispute his findings and spawn their own scientific research, that Lombroso became known as the father of modern criminology. Before his scientific research, most theories about crime were based on moral and religious grounds.

Lombroso’s Glove

The idea of truth detecting—or lie-detecting—emerged as a legitimate scientific practice in 1895 when the controversial Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso (founder of the Born Criminal Man theory above) came to the conclusion that sudden changes in blood pressure could be an indicator of a person lying.

As part of his research, Lombroso developed a device called Lombroso’s Glove. It was used to measure changes in a suspect’s blood pressure. Those findings were recorded on a chart to gauge whether or not a person was likely lying.

While Lombroso’s device never developed beyond its infancy, other researchers and criminologists followed up on his theory, developing other machines to detect when a person was lying. Some of the leaders in making these devices included Dr. John A. Larson, Leonard Keeler and William Marston, a psychologist who was considered the father of the polygraph machine.

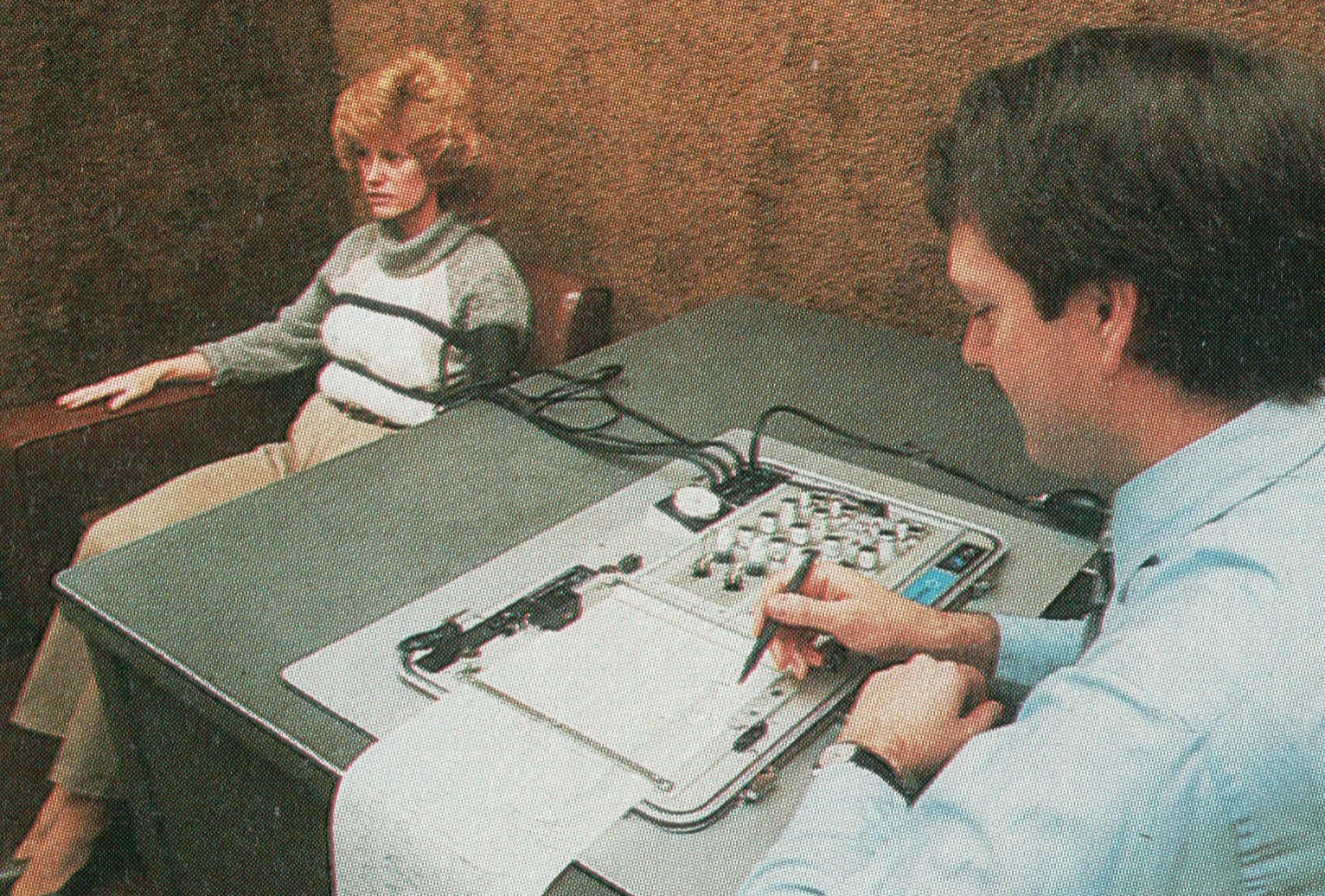

Modern Polygraph Test

During World War I, the United States government commissioned William Marston to develop a method for ensuring that prisoners of war were telling the truth when they were interrogated. Drawing upon the previous work done by an Italian criminologist, Marston incorporated the testing of blood pressure during the interviews with the prisoners. His simple device, which was called a systolic blood pressure test, was attached to the subject’s arm while a person asked a series of questions to determine if there was a change in blood pressure—therefore, indicating deception.

It didn’t take long for the effectiveness of the device to be called into question. Although Marston claimed that the device led to “remarkable results,” John F. Shepard of the U.S. Department of Science and Research had his doubts. “The same results would be caused by so many different circumstances, anything demanding equal activity (intellectual or emotional), that it would be practically impossible to divide any individual case,” Shepard wrote in one report.

However, Marston was undeterred and continued to promote his Lie Detection Test, as it was now called in media reports. He later used his device as part of a 1923 court case — Frye vs. United States. James Frye, who was on trial for murder, first denied he was guilty of the crime, but then later gave police details of the killing. According to Marston, he then recanted, stating that he only confessed because he was promised part of the reward money in exchange for his confession. Marston’s lie detection device found that he was telling the truth.

Since Frye’s alibi witness refused to testify, the Marston’s lie detection findings were critical to the case. By this time, Marston’s lie detection device had received national press. So, it was no surprise that the courtroom was overflowing with a crowd on July 18, 1922 when he was scheduled to testify about his findings with Frye.

However, before Marston could testify, Chief Justice Walter I. McCoy refused to entertain any findings from the device. He said that the real experts at deciding whether or not someone is telling the truth is the jury — not a lie detector test. He then said he would read more about Marston’s research after “he got back from vacation.”

Ten days later, Justice McCoy sentenced Frye to life in prison.

On appeal, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the lower court’s decision with this statement: “The systolic blood pressure deception test has not yet gained such standing and scientific recognition among physiological and psychological authorities as would justify the courts in admitting expert testimony deduced from the discovery, development, and experiments thus far made.”

Although the lie detector test, now frequently called the polygraph test, has been honed and refined, the Frye v. United States set a precedent. While the polygraph continues to be used in certain settings, the findings of polygraph tests are not admissible in court.

The lie detector test underwent numerous evolutions as more people became interested in Marston’s highly publicized device.

In the Frye case report, a summary of how the test was administered was documented as follows: ”In other words, the theory seems to be that truth is spontaneous, and comes without conscious effort, while the utterance of a falsehood requires a conscious effort, which is reflected in the blood pressure. The rise thus produced is easily detected and distinguished from the rise produced by mere fear of the examination itself. In the former instance, the pressure rises higher than in the latter, and is more pronounced as the examination proceeds, while in the latter case, if the subject is telling the truth, the pressure registers highest at the beginning of the examination, and gradually diminishes as the examination proceeds. — Frye v. United States, No. 3968, (D.C. Cir. 1923)

In 1921, John Larson, a police officer and a PhD student in physiology, and Leonard Keeler, also a police officer, built upon Marston’s work by creating what they called the cardio-pneumo psychograph. The device measured physical responses — both respiration and blood pressure — in response to questions.

Keeler added the use of ink and paper for an automatic recording of the results. Keeler’s version, which was patented in 1931, was further improved to measure changes in skin reactivity, including sweating.

According to the American Polygraph Association, four sectors continue to use the polygraph: Law enforcement agencies, the legal community, government agencies, and the private sector. However, the Employee Polygraph Protection Act of 1988 (EPPA) prohibits most private employers from using polygraph testing to screen applicants for employment. It does not affect public employers such as police agencies or other governmental institutions.